Thermodynamics … Humbug!

January 27, 2021 | By Curtis Bennett

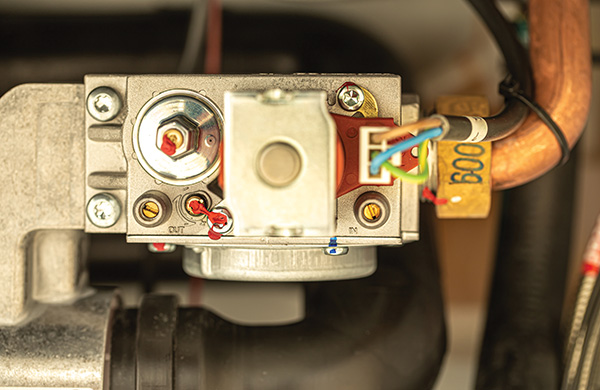

Troubleshooting boiler controls issues requires taking methodical steps, but sometimes the solutions are more obvious than you think, like a simple hole in the wall.

(Getty Images)

My wife tells me that I am way too literal, and when she says it, it’s not a compliment.

I tend to look at things as 1’s or 0’s, on or off, open or closed, true or false. That’s how mechanical controls work, at least on the inside, and that’s where I spend my days.

There are not too many control issues that fool me anymore. Not that I am some super troubleshooter, just that I take the fool me once , shame on you, fool me twice, well that’s my bad for not seeing the same issue happening again.

So thankfully most, and I say most, of my good troubleshooting mishaps occurred when I was familiarizing myself with this industry. Now don’t get me wrong, I am still learning all the time, but in certain situations familiar patterns appear and I am now able to see them quicker.

Troubleshooting is not about knowing every possibility to figure out a problem, it’s about taking the right steps or asking the right questions to see the problem as clear as possible.

Many times I’ve been on the phone with a customer only to get near the end of our conversation before I ask what I believe to be an obvious question—only to find out it was not so obvious to them. So today let’s take a look at a couple troubleshooting doozies that I’ve encountered over the last few years.

Troubled Shooting

First things first, story time. To be honest I thought I was out of “shocking” stories to share, but it turns out I am not, they just keep happening to me. I’m not sure if it’s because I like electricity or I’m just a sucker for punishment. This story starts with my son’s friend’s homemade Taser. Yes, all good stories start like that!

I have no idea where he got the parts for it, but he did. He found the instructions online and made this Taser. After he built it my son and his friend had tried to zap themselves on the toe or somewhere really far from their heart, because they had heard from someone to stay away from the heart. They said that the zap hurt, but nothing too bad.

So I was over at the friend’s house having dinner, as I am friends with his dad, and I said “go get that Taser!”

So the young man goes and gets it and presses the button, to just show me the raw power as it makes this nasty zapping sound. If you’re of my era or older you will remember bug zappers and the crazy sound they made when a moth flew into range. It was something like that.

Anyways, I said ok I’m going to do it. I showed him the area on my arm to “taze” me, and I told him to give’r. Well it hurt, it really hurt. He “tazed” me on my forearm and it made my whole hand curl up. I think he held it on a little too long, but I probably would have done the same thing.

It left a little mark on my arm, and of course everyone laughed hard. At the end of the day, if this is what it takes to get stories for articles, so be it. This episode was a completely different type of ‘troubled’ shooting … now I’ll get back to where I was originally heading.

Coding Conundrums

I still troubleshoot at our business on a daily basis. Computer coding is notorious for bugs. Some bugs are bigger than others, and I have spent days on a single, sometimes seemingly small coding bug, going through every possibility only to find out it wasn’t even my fault. It was a compiler issue.

Let me tell you, nothing is more frustrating than finding out a huge bug is not even your fault, but likewise a huge relief that you’re not a bobble head in making a stupid mistake for days. However, I have had those as well and they sting badly.

One approach I take to troubleshooting is talking things out. I will often just sit down with someone in the office and explain my problem. I summarize it as best as possible, and then talk it out. More often than not while explaining my issues, or the coding dilemma, I will see the answer.

But OK, I’m not here to talk about coding issues. So let’s talk real world mechanical control issues, or maybe not the control but something that masks as a control issue. I have two good ones, so let’s jump in.

Limitless

I enjoy what I do, but when I can’t figure something out it drives me crazy. While designing our original boiler controls, I spent countless hours in boiler rooms learning how things work and why they do what they do. I was “green”, so I was learning more each day about controls, but I was not entirely up to speed on the equipment internals.

When the control sends the signal to turn a boiler ON/OFF, the appliance is supposed to turn ON/OFF. The issue we had was that our control was turning the boiler on, but the boiler was shutting off early. So where do you start?

Well, make sure the control is actually turning on the boiler. We do that by doing a continuity test at the connection at the control. Now don’t do a continuity test with the boiler wires hooked up. Resistance does not work when there is voltage present, and the boiler wires “most likely” have 24VAC on them.

So I tested the control, we had continuity. So we move down the line and perform the same continuity test at the boiler. This test was good as well. The control is still turning the boiler on, and the wiring is good. Next, we make sure the boiler is still powered. Yep, still powered.

If a boiler does not have any flow, the flow switch will not prove and the boiler will turn off. But guess what, good flow. It was getting a little perplexing at this point, so I needed to dig deeper into the boiler and its onboard controls.

After some digging and reading, it appeared everything was good. Remember, the problem was not turning the boiler on, but that it was turning off before the control was ready to turn it off.

At this point I started to look at the wiring diagram inside the boiler. It showed something I did not think about, and to be honest, because I was not so familiar with the inner working yet this was not too obvious. The internal limits of the boiler.

You guessed it, someone had turned down the limits and they were set lower than our control. Eureka!

Now this wasn’t a five-minute conclusion, this was most of a day to get to this solution. Something so simple.

It’s interesting when you examine the problem-solving process we go through: it seems to start slow and methodical, and then gets a little more “frantic” as the day goes on. Luckily this problem was solved and was added to the database of encountered issues in my head.

Conduit Control

This next challenge was not as obvious, but equally as perplexing. I travelled to a lot of job sites when our company first started to sell controls. Sometimes I was just helping out, because we were new but also because there were legitimate issues and we wanted to have great customer service.

So this call was about the control going into warm weather shut down (WWSD) when it should not be.

The starting point was at the control. Check the wiring, look at the wiring for a bad connection, or even worse an intermittent connection! But they all came up negative.

Then we checked all connections at the outdoor sensor and heated it up a little to watch the control show the correct number. All was good. Next was to take a known good sensor and hook it up to the control to see the result. Guess what, it works as well.

Keep in mind that thermistor testing takes a little time. You need to watch to ensure there is a change over time, and that the numbers settle in where they should. So we were getting to the end of the day. I will point out that this was a warm day, around 15C outside, so we were not in WWSD and we should not have been.

So I needed to come back the next day. The next day the temp was quite a bit colder, but the first thing I noticed was that the outdoor temperature on the control was not showing as cold as it should. So we went outside to look, but we were on the north side of the building so there was no sun exposure. I know that’s what you were thinking.

So what the heck could it be? The sensor was located outside the wall from the boiler room. It was attached well, they even used conduit to go from inside to outside! Normally, and take “normally” with a grain of salt, you don’t use conduit. At least I had not seen it done before. Usually it’s just drill a hole to the outside and run the wire.

Sometimes a simple hole in the wall is the answer. (Getty Images)

So it turns out this was a good lesson in thermodynamics—temperature wants to naturally equalize. So what was happening is that because they had used conduit from inside the room to outside, the heat from the room was moving outside and heating up the outdoor sensor.

WHAT!!!!

Yes, that was it. There was a big enough opening that the heat could transfer. That’s why when you just drill a hole, the wire takes up most of the space so no heat can move through the wall. But with the conduit, the wires did not take up enough space to stop the heat transfer out to the sensor.

You did notice that the first day I was there the temperature outside was pretty close to the temperature in the boiler room. That is why we could not find anything wrong. It was not until the correct situation arose that we could even start to look at different options.

Help Me

At the end of the day troubleshooting is actually fun. We get a rush when we find the problem, especially if it was a doozy.

One of the biggest issues in troubleshooting is trying to replicate an issue. It’s actually where we spend most of our time when troubleshooting at the office. If you can’t replicate the issue you can’t find it.

Good, detailed and accurate information, whether from yourself or from someone on the phone, is pivotal to finding a solution. To quote Jerry Maguire, “Help me! Help you!” Thinking about that movie actually has me laughing out loud. It had me at “Hello.” <>

Curtis Bennett C.E.T is product development manager with HBX Control Systems Inc. in Calgary. He formed HBX Control Systems with Tom Hermann in 2002. Its control systems are designed, engineered and manufactured in Canada to accommodate a range of hydronic heating and cooling needs commonly found in residential, commercial and industrial design applications.

Curtis Bennett C.E.T is product development manager with HBX Control Systems Inc. in Calgary. He formed HBX Control Systems with Tom Hermann in 2002. Its control systems are designed, engineered and manufactured in Canada to accommodate a range of hydronic heating and cooling needs commonly found in residential, commercial and industrial design applications.